History of Remembrance

For a museum curator, there are few things more gratifying than inadvertently discovering a famous artist’s unseen work.

But for Karen Haas ’78, what began with a casual phone inquiry about a single photo by the late photographer Gordon Parks ultimately led to a stunning new book of Parks’ unpublished photos from 65 years earlier, a sad but enlightening road trip through the Midwestern United States, and one of the most powerful exhibitions the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, has ever produced. None of it could have been predicted.

Haas serves as the MFA’s Lane Curator of Photographs; she oversees a massive permanent collection of nearly 7,000 prints from virtually every era of photography, with particular emphasis on the work of American modernist photographers such as Ansel Adams, Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham. She is also the recipient of the 2016 New England Beacon Focus Award from the Griffin Museum of Photography.

The Parks exhibition, which Haas curated in 2015, sprouted from a museumwide book project that Haas and her fellow curators from other departments were working on to showcase the works the museum held from various African American artists.

“We had this one Gordon Parks photo of a young couple outside of a segregated movie theater in a small town, but the information we had was extremely limited, and I couldn’t figure out where it was from,” Haas says.

A natural stickler for detail and a bit of an amateur detective, Haas set out to learn as much as she could about the mysterious photo. She made a trip to the Gordon Parks Foundation in upstate New York, where she was shocked to learn that her mystery image was part of an assignment for Life that Parks had taken on in 1950 but that had never been published, for reasons that remain unclear.

“I became obsessed with this whole story,” Haas says. “I went to Kansas, where the Parks archives are, and I read through all of his handwritten notebooks. I looked at the telegrams and correspondence related to that particular assignment [with Life], and I began to piece together the puzzle.”

In 1950, Parks was living in New York City and working as the first and only black staff photographer for Life. When his editors asked him to craft a photo essay on school segregation—a major national issue in the years leading up to the landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education—Parks suggested that he return to his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas, in an effort to track down his 11 fellow classmates from elementary school, none of whom he’d heard from for more than 20 years. To explore segregation through such a personal lens was a novel concept at the time, but Parks was a rising star, and his editors agreed it would make the piece more powerful.

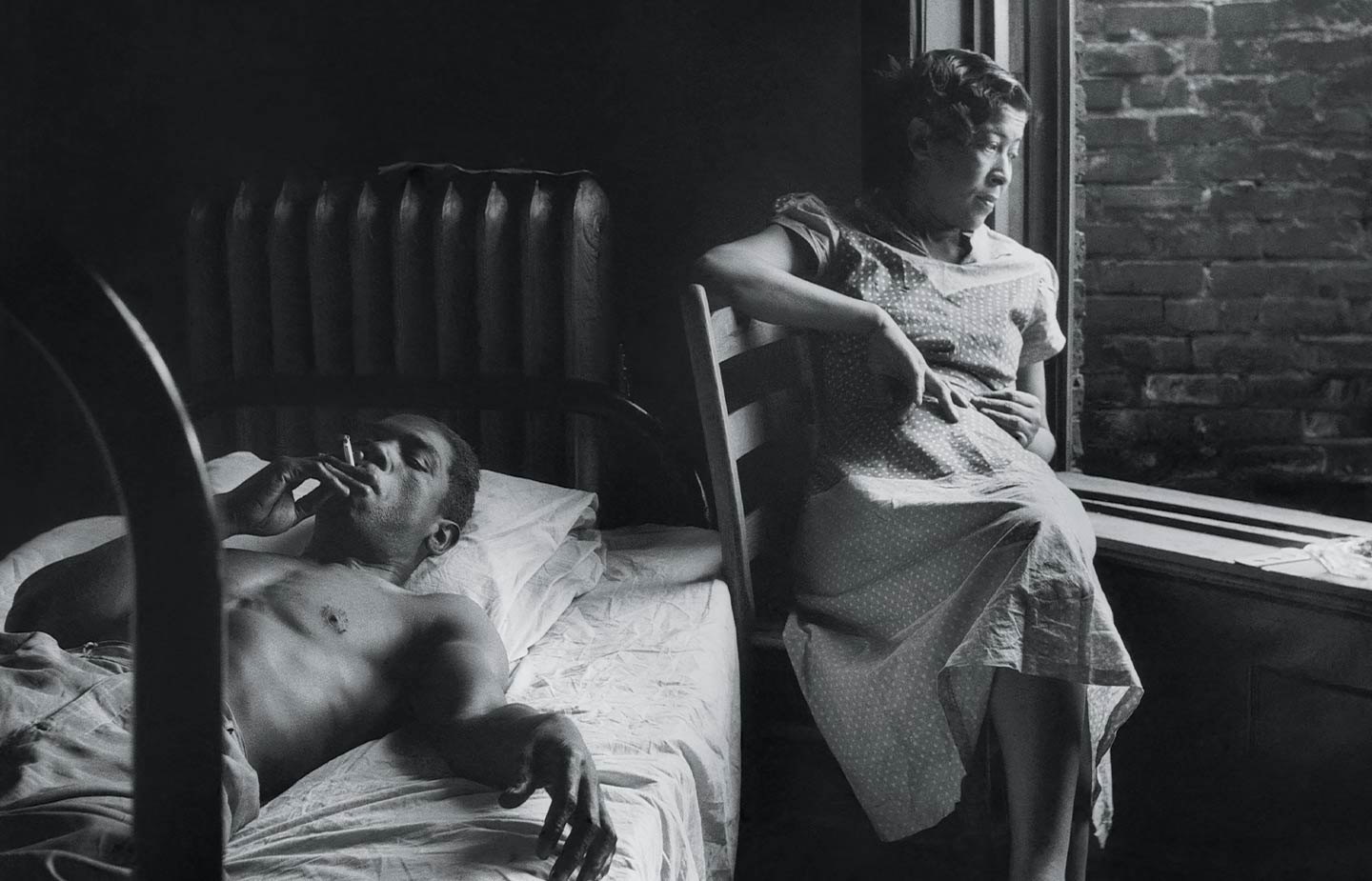

Sadly, Fort Scott, ravaged by decades of racism, violence and economic devastation, was still home to only one of Parks’ classmates when he arrived. Like millions of other black Americans since 1916, the rest had joined the Great Migration in search of better lives in urban areas such as Chicago, Detroit and New York. Nonetheless, Parks managed to track down nearly all of his classmates in other cities, and they agreed to be shot in raw, occasionally heartbreaking settings. Those photos—more than 30 altogether—made up “Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott,” the extraordinary exhibition Haas curated.

“What I loved about those images was that they were photographs of families and of people who were in different life situations when Parks found them, but they were taken with so much respect and strength, and there’s so much power in the trusting gazes you can see in many of them,” Haas says.

She was so inspired by the photos and the stories of each of Parks’ classmates that she hired a genealogist and recruited her husband—a photographer who also works at the MFA—to join her on a road trip in search of any living descendants of the men and women in Parks’ 1950 photos.

They didn’t meet with much success in finding any of the relatives, and all of the original homes of Parks’ classmates had been torn down, but Haas says the entire experience had a profound impact on her, both personally and professionally.

“It was a huge turning point in my career, and it really inspired me to focus as often as I can on making our collection more diverse,” she says. “That moment of realizing what the Gordon Parks exhibit meant to our community and seeing people and hearing from people who said it was the first time they ever saw photographs in a museum that truly look like their families—that was deeply moving.”

That philosophy has been on display in the years since, with exhibitions like “(un)expected families” (2017), which showcased a variety of photos challenging the conventions of traditional family portraits and celebrating the diversity of families today.

And earlier this year, Haas curated a critically acclaimed Ansel Adams exhibition that explored the legendary landscape photographer’s work through a new lens, by including some interpretations of his photographs by contemporary artists, who offered commentary on climate change and other modern environmental issues.