The Flash of Light

David Rubin ’85 writes about how Stephen Hawking’s theory of everything influences landscape architecture.

Insomnia keeps three books by my bed. Sleeplessness is a trait inherited from my late father, who never slept well except on Sunday afternoons, with a game on and a soft couch in proximity. My burgeoning design practice, now six years old, keeps my head full of voices in the early morning hours—lively discussions I can’t seem to resolve without distraction—so hereditary insomnia means lots of hours with an opportunity to read.

At the bottom of the pile is Juhani Pallasmaa’s The Eyes of the Skin, an essay that describes the author’s concern for form-based architectural design—solutions that forget the human condition when defining enclosure. This is my constant reminder that landscape constructs are informed by the creation of space, not objects, and that successful landscapes create environments in which human beings feel comfortable enough to engage in conversations with one another. Places that are loved in the hearts and minds of citizens are those that will last, and I’m determined that my grandnieces and grandnephews will know me through the legacy of human-focused design works. Describing form is easy; defining space is hard.

During my tenure at the American Academy in Rome, a fellow Rome Prize recipient in the arts suggested I read Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations. I had recently separated from my old practice and partnership, and my fellow Fellow encouraged me to read the ’70s Penguin edition of the classic self-reflection so that I might understand what it means to be a good leader of my own newly formed studio, Land Collective. Aurelius was the last “good” emperor, who spent a significant part of his life in the lands now called Austria defending his known civilization against the unknown. Uniquely, he knew himself to be human, not a god, and wrote a personal log of emotionally resonant, reflective thoughts. His writings, never intended to be published, are filled with love and loss, fear and loathing, and a thoughtfulness that reveals how little human beings have changed in 2,500 years. Technology certainly has. But human behavior is, within reason, predictable. I keep the Hicks brothers’ version close now. The accessible, contemporary language brings Aurelius’ thoughtfulness into the 21st century.

At the top of the pile is Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time. This accessible narrative about the origins and future of our universe (and beyond) speaks to Hawking’s life goal of finding the unifying maths that connect Einstein’s theory of general relativity with the study of quantum physics. For the physicist, this unification would be the theory of everything and a capacity to understand the poetry of why? Though Hawking’s desire wasn’t realized in his lifetime, the poetics and joyful aspiration of finding reason amidst the nearly intangible—that the union of two seemingly disparate ideas could provide a level of enlightenment that would bring great understanding—was an admirable and brilliantly conceived goal.

This notion of describing a universal theory, something that explains EVERYTHING, resonates in the darkness of the night, especially on summer evenings at the Jersey Shore, where my husband and I have a cottage, where limited light intrusion in the night sky allows the Milky Way to be visible. There is humbling vastness in the vacuum of all of that space, and great distances between points of light. It is an extraordinary display, reaching from horizon to horizon in a wonderfully subtle arc.

It might seem odd to believe in a correlation between Hawking’s work and my own. As a landscape architect who focuses on an empathetic approach to design problem-solving, equity in urban environments and inclusiveness, I am determined to design humanist constructs that allow very different sorts of people to socialize where they might not typically, a challenge in contemporary society worthy of exploration.

My work is not about curb appeal, although aesthetics is part of my design tool kit. It is also not the progressive verb “landscaping,” the word utilized in abundance on weekend home-fix-it shows. If you take away anything from these writings, please don’t ever describe the marriage of anthropology, sociology, ecological sciences and design as the sauce that is poured over a building to hide all of the mistakes and beautify its surroundings. Landscape architecture is a complex amalgam of disciplines, and landscape a politically charged social construct.

When I explain to people what I do, I start with the image of an apple on the ground, having fallen from a tree. And then I share an image of an apple orchard with a canopy-wide circle of apples immediately below where they once hung from that tree, perfectly arrayed on the ground. And I remind people that this red Newtonian orb is bound to the earth through gravity. I believe in gravity. It’s a universal truth. As such, it binds us all to this earth, this common ground. And this common ground is where we all stand, unified. Landscape is the most equitable discipline. It is the least-expensive means by which to affect the greatest number of constituents, particularly in an urban environment. When more and more have less and less, the connective tissue on which we stand has the potential to positively inform the breadth of constituency.

So, where does Hawking fit into this equation of gravitational pull? I actually think Steven Hawking secretly wanted to be a landscape architect. He didn’t realize this lofty goal in his lifetime, and it might just be my fantasy that there is any semblance of truth to this notion of mine, but here we go.

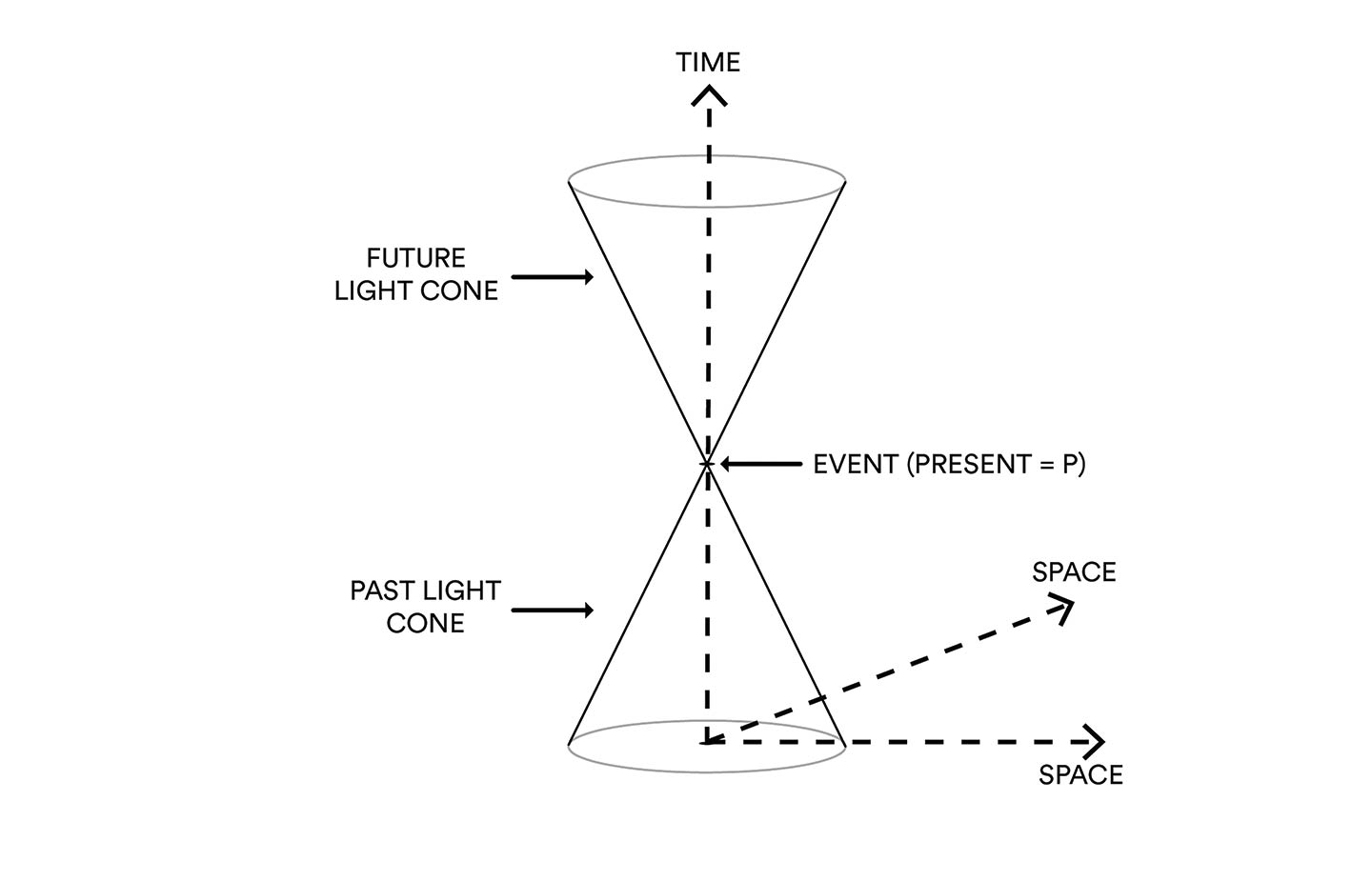

In his effort to describe his understanding of the theory of general relativity, Hawking references the speed of light as the one true constant in our known universe. He generates diagrams to describe an event, the brilliance of a momentary flash that travels outward at 6.706e+8 miles per hour in all directions to create an ever-expanding sphere. He maps it over time and cuts the sphere at intervals as time moves forward. In this process, a cone is formed, like a perfect confectionary. He describes this as a “future light cone”—all the things the expanding light will inform as it progresses outward into the universe.

Conversely, everything leading up to that moment of flash is a “past light cone”—all the events that informed that great, constant expansion funneling into that singular event. Everything that informs the moment is the relevant past; everything that is informed by that spectacular moment continues on ad infinitum. And everything else, those moments not informing, nor informed by, the flash are called the “elsewhere of P”: the elsewhere of the present. The elsewhere of P is everything not relevant to the momentous “flash.” It is the vacuum of space that separates the event, and potentially all of us.

And so, two cones meet at the pointy ends, everything leading up to and everything leading away from a significant event at the present moment. And the light of the future keeps moving outward in all directions.

The speed of light is constant, the one known thing, moving out in time at a rate of speed that is understood. But even Einstein realized that time is relative: Every person perceives time differently. You know this to be a relative truth. Think of your childhood, and those long, heady, summer days that never seemed to end when you were out catching fireflies. They were infinitely long days. Compare that to your adult workday. It can be compressed into a fleeting moment that passes imperceptibly or else expanded into an endless, elongated series of events that never seems to conclude. And yet the number of hours in a day remains the same.

So, if we all perceive time differently, those moments of spherical expansion move out relative to our individual understanding and position. We all stand on the same ground at the present moment in time. We all have our own future light cones, expanding out from the light within each of us. We all have a past that informs the present day, everything leading up to the moment of time that represents today, this day, this very moment. Each of us has our past and future light cones. And the elsewhere of P is the emptiness that stands between each of us.

And it’s that vacuum that I want you to appreciate. It can be vast.

Using the past and future light cone diagrams, we can map the cone on a plane where the flash is the point of tangency. Acknowledging, as Einstein did, that everybody experiences time differently, we can begin to see something that describes each of us. We each understand time differently; each of us has these momentary flashes of light that define the present and inform the future. If we map these to the plane of landscape—the connective tissue that unifies us. that thing on which we all stand—then as we move through time, the ultimate goal is the unification of those mapped spheres describing our future. Eventually, there is a point of tangency and overlap that represents the union of those expanding spheres. These become the opportunity for connection and conversation, and the expanding light in the present moment becomes the potential spark of connection between us.

The study of quantum physics focuses on the anticipated patterns found within a seemingly random expression of atoms and subatomic particles. While one is mapping the randomness over time, predictable patterns begin to emerge. Human movement is not dissimilar. We move through time in seemingly random patterns, but actually we are fairly predictable as we move from home to work, or work to school, with the occasional diversion to the cleaners, convenience store or coffee shop. When you consider that each of these future light cones might represent each of us, and you marry the theory of general relativity to the patterned randomness of quantum physics, you find opportunities for serendipitous encounters fostering unanticipated conversations that just might surface the big idea that saves the world! One moves through time, responds to the quality and character of a well-designed space, meets another human being in that context, and says, “Hello”—and a conversation begins. That’s why Hawking wanted to be a landscape architect. In his aspirations for understanding the universe, he actually described all of us and the prospective power of connection.

And so I believe in gravity, and light, and serendipity, and in an effort to problem-solve on behalf of my clients, create humanist constructs where very different sorts of people—say, a chemistry professor and a young protester—might find themselves sitting proximate to one another, and as a result engage in conversation, and through that conversation kindle an idea, one that might save the world. And in an era of nationalism and xenophobia, it is conversations that elevate culture. We are more alike than dissimilar, a range of humanity separated only by minute particles of DNA and cultural nuance.

What Hawking described is actually what I do, and it’s kind of wonderful. In his depiction of the physics of light and pattern, and in his aspiration to understand what happens at the point of tangency, Hawking delivered a poetic rendering of my practice. So it’s that flash of light, that thing that resonates from within us moving out in all directions that has the potential to cultivate conversation through chance encounters. As a highly empathetic, secular humanist, I believe that there is light within each of us that defines us as individuals, and when you can work as a landscape architect to unify those flashes of light, incredibly powerful, beautiful things happen.

Perhaps Steven Hawking wasn’t exploring physics. Perhaps he wanted to be a landscape architect. With all due respect to physicists and those better versed in the calculations of matter and the (now realized) imaginings of black holes, I offer my late-night interpretation of Hawking’s aspiration to find the theory of everything—and why he speculated on what I do every day.

David Rubin is a landscape architect who owns the design firm Land Collective.