Global Genres of Modern Iran

Forty years after the Iranian revolution, Assistant Professor of English Marie Ostby is showing that Iran’s literature is as rich as ever.

When Marie Otsby was five years old, her family traded the borderline oceanic climate of her native Oslo for the subtropical environs of Islamabad, Pakistan.

Ostby’s father worked for the United Nations—a career that led her around the world growing up and would eventually help to forge a profound connection with the culture, art and literature of the Middle East.

“I spent seven years in Pakistan and graduated from an American high school in Islamabad, but it wasn’t until I was in college that I began to really fall in love with Iran,” Ostby recalls.

By then, Ostby’s father was stationed in Tehran, and she spent two summers living there and working with some local AIDS awareness organizations while building Farsi language skills.

“It might sound a bit silly and romantic, but as a literature major at the time, it struck me how central literature was to everyday life there, and that was exciting to me,” she says.

Ostby joined Connecticut College in 2015 as an English professor, and is also a member of the Global Islamic Studies program, which she says played a central role in bringing her to Conn.

“We’ve been meeting in a faculty seminar to renovate and enhance the Global Islamic Studies curriculum and to share research with each other, which has been great,” she says. “Next year we have three seminars that we’re opening up to the whole faculty for expanding the study of Islam and Muslims across the curriculum, one of which I’ll be teaching, so I think the program is really heading in an exciting direction.”

Her current book project, tentatively titled, The Global Genres of Modern Iran: From Travelogues to Twitter, is an ambitious research effort that will explore a range of topics relating to Iranian literature, Western misconceptions about Iran, and the transformational effect of technology and social media on Iranian writers in exile, and will expand on her long-held interest in the Iranian diaspora.

“Twitter, for example, has been fascinating to watch, because there have been Iranian American poets communicating with working poets in Iran and sharing their work that way, even though the sanctions, of course, prevent Americans from publishing in Iran through formal channels,” Ostby says. “So these types of diasporic writing connections are being made every day.”

Ostby hopes her book will challenge the stubborn trope so common in the literature and films Americans have been bombarded with over the past 40 years that depict a one-dimensional Iran plagued by Islamic extremism and oppression.

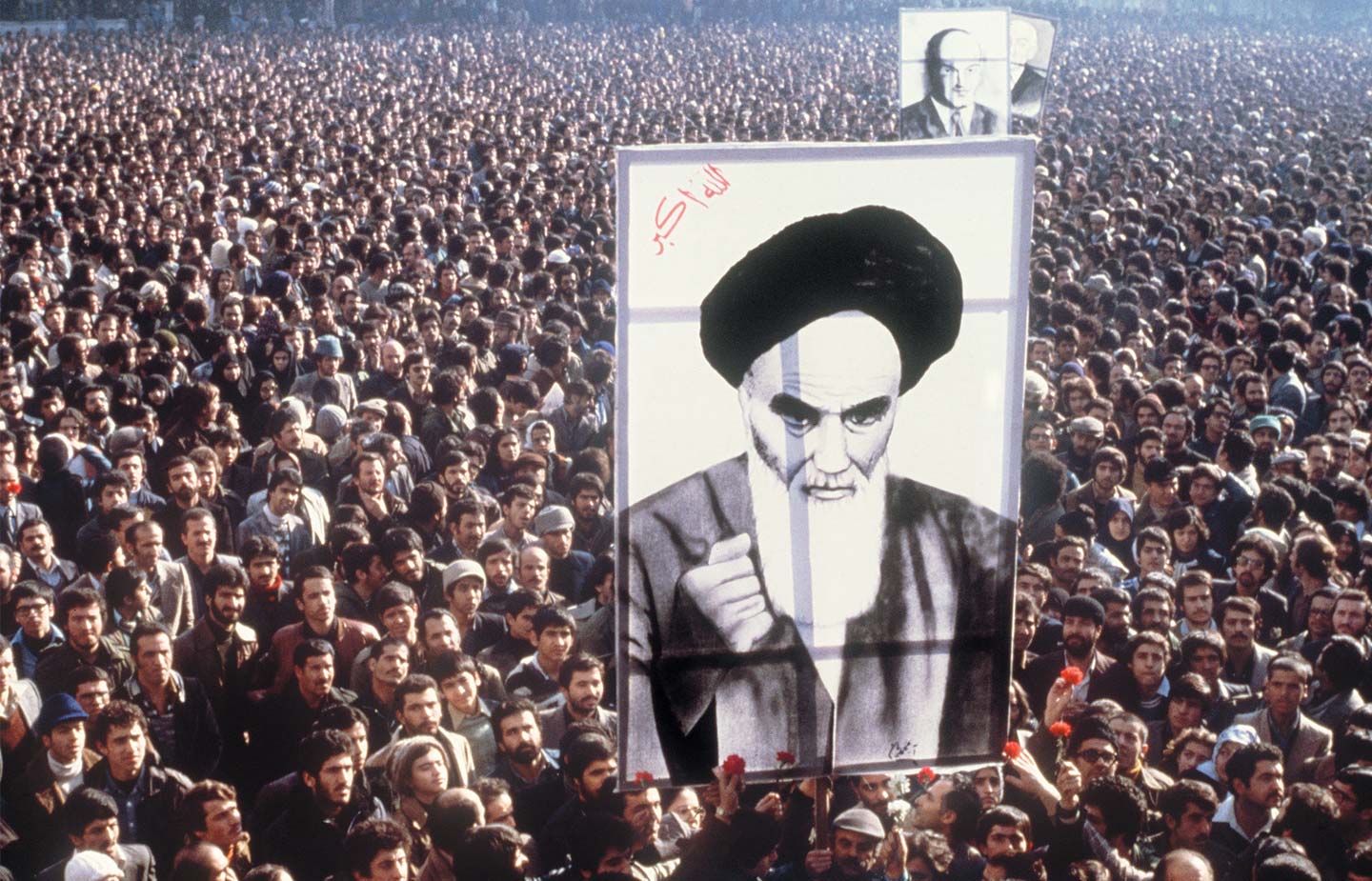

One frustrating reality that Ostby points out is that since the 1979 revolution, the dominant literary genre that Americans have relied on to shape their perceptions of Iran is memoir—specifically memoirs that focus on stories of daring escape from Iranian captivity. Ostby says the picture is far more complicated and nuanced, and that obstacles to free expression didn’t suddenly manifest after the revolution.

“Many people seem to think that prior to the revolution, [in the time of] the Shah, Iran was experiencing Westernization and modernization,” Ostby says.

“But it’s important to remember that the Shah had a ruthless secret police force that tortured and imprisoned people at the same rates as we saw after the revolution, and dissidents, journalists and artists were just as afraid for their lives under the Shah as they were after the Ayatollah took over following the revolution.”