Forget Me Not

Distractions are all in your head, says Psychology Professor Jeff Moher.

If our brains had an unlimited capacity to process information, “Where’s Waldo” would be no fun. We’d simply open the oversized children’s book and our brains would zero in on the little guy in the red and white stripes.

“We just can’t look at something and immediately know everything that is going on,” said Assistant Professor of Psychology Jeff Moher.

Instead, we move our attention through the image and sort through the distractions to find exactly what we are looking for.

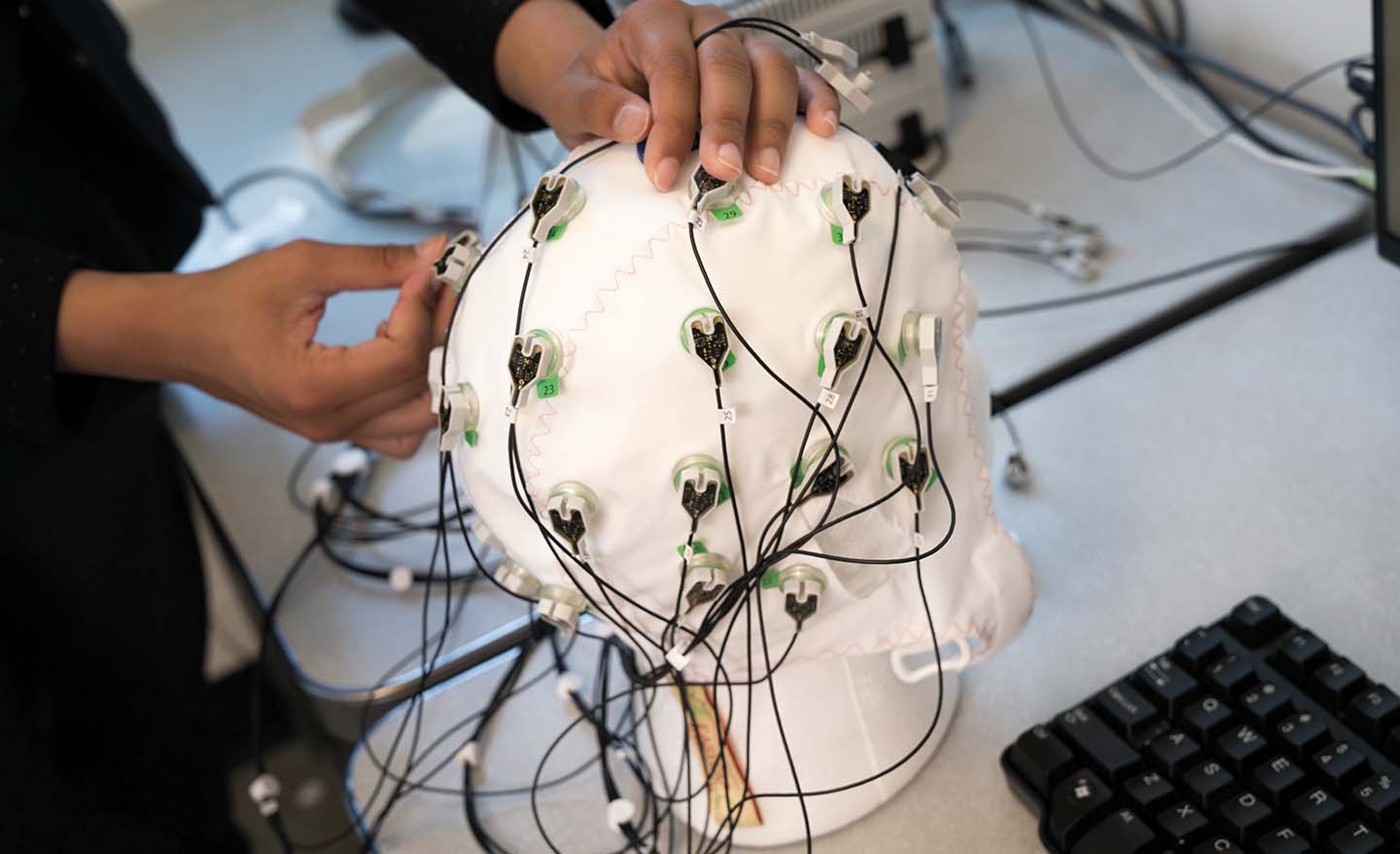

Moher uses both behavioral and neurophysiological methods to study when distractions are likely to occur to find out how distractions might be avoided. He has spent much of his career studying how the brain separates relevant information from irrelevant information and what impact salient distractors—objects that stand out because they contrast with their environment—have on attention, particularly when a subject is searching for something visually.

Now, he and colleagues from Brown University are studying a different type of distraction entirely: the kind that’s all in your head.

With a $357,061 grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, part of the

National Institutes of Health, Moher and his colleagues will examine the link between sustained attention and motor output in an attempt to answer what happens to physical movements when your mind wanders.

Moher and his team, including his students, will test whether people completing physical tasks that require them to maintain focus for a long period of time are more likely to have slower response times or make mistakes when their minds begin to wander. They will also be looking at whether or not subtle changes in pupil size can indicate someone is losing focus, and use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to look at whether changes in the brain networks involved in drifts of sustained attention are linked to changes in hand movements.

“The ability to diagnose when a person is losing focus by measurements of simple motor movements or pupil size would be highly valuable,” Moher said. “Just by looking at a physical part of the body, we could say, ‘This person is not quite as focused as they want to be and they’re probably going to make an error.’”

That hypothesis isn’t entirely new—some later model cars will automatically alert you if your steering wheel movements become less consistent and you begin to drift out of your lane, for example. But Moher’s research could have implications for the diagnosis and treatment of brain disorders known to involve deficits in attention and/or action, including ADHD, schizophrenia and stroke.

“One of the big risks after a stroke is falling, because of the lack of motor coordination,” Moher said. “If we can better understand how the motor system is linked up with difficulties with sustained attention, that might be helpful in figuring out the best way to rehabilitate.”