Reading the Rainbow

A Conn education class expands local K-8 classroom libraries.

Who decides what information is available in a library? According to the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, not the government—and that includes local school boards. And yet, in many school districts across the United States, books are being pulled off the shelves.

The American Library Association recently reported 1,269 demands to censor 2,571 unique titles in 2022, up from 729 demands to censor 1,858 unique titles in 2021, and a record since it began tracking data more than 20 years ago. Of those titles, the vast majority were written by or about members of the LGBTQIA+ community and people of color, and 58% of the reported challenges targeted books and materials in schools.

In New London, Visiting Assistant Professor of Education Karen Pezzetti and the students in her “EDU 313: Children, Books and Culture” class are bucking that trend. They are working with partners in local elementary and middle schools to add more diverse offerings to classroom libraries.

Pezzetti’s class received a $2,000 grant from Eversource to support the project in February, and another $1,000 in March from Lydia Morris ’88, who made the donation after reading about the project on Conn’s website. The $3,000 was divided evenly across their 12 partner classrooms, resulting in a $250 budget for each.

Morris, who works on the business side of K-12 public school education, told Pezzetti she was “glad to see action toward supporting kids by expanding—and not restricting—what they read.”

This semester was Pezzetti’s first time attempting the project, which involves her 26 students working in pairs with five local schools: Nathan Hale Arts Magnet Elementary School, Harbor Elementary School, Bennie Dover Jackson Middle School, and the Regional Multicultural Magnet School, all in New London, and Charles Barnum Elementary in Groton.

Most of the partner schools have some form of a school library or media center, but they are often understaffed and have limited hours for students, Pezzetti explained. That’s where classroom libraries can fill a need.

“All kids should have access to great books that reflect their own lives, open doors to other worlds and inspire a love for reading,” Pezzetti said.

“We read a chapter of a book called Teaching with Children’s Literature: Theory to Practice in which the authors contend that elementary classroom libraries need at least 1,500 appealing, well-organized books to support the reading of a whole class over the course of a school year. When my students did inventories in their partner classrooms, we learned that more than half of the classrooms we worked with had fewer than 100 books, and one only had eight.”

To prepare for the initiative, Pezzetti’s students interviewed Alison Mitchell ’95, the Youth Services Librarian at Somerville Public Library, West Branch, in Massachusetts. Some students worked to develop their expertise in certain types of children’s literature, while others volunteered once a week in the partner classrooms to get a sense of what books that particular cohort of students would benefit from most.

During class meetings, the students read a wide range of children’s books, including those that are contentious and sparking debates. “Some have even been banned in some schools and libraries,” Pezzetti explained. “For example, we read books with trans and nonbinary protagonists. We also read books that cover hard history, like one about the Tulsa Race Massacre in Oklahoma in 1921. The students were working on developing their judgment about what books are appropriate for which contexts.”

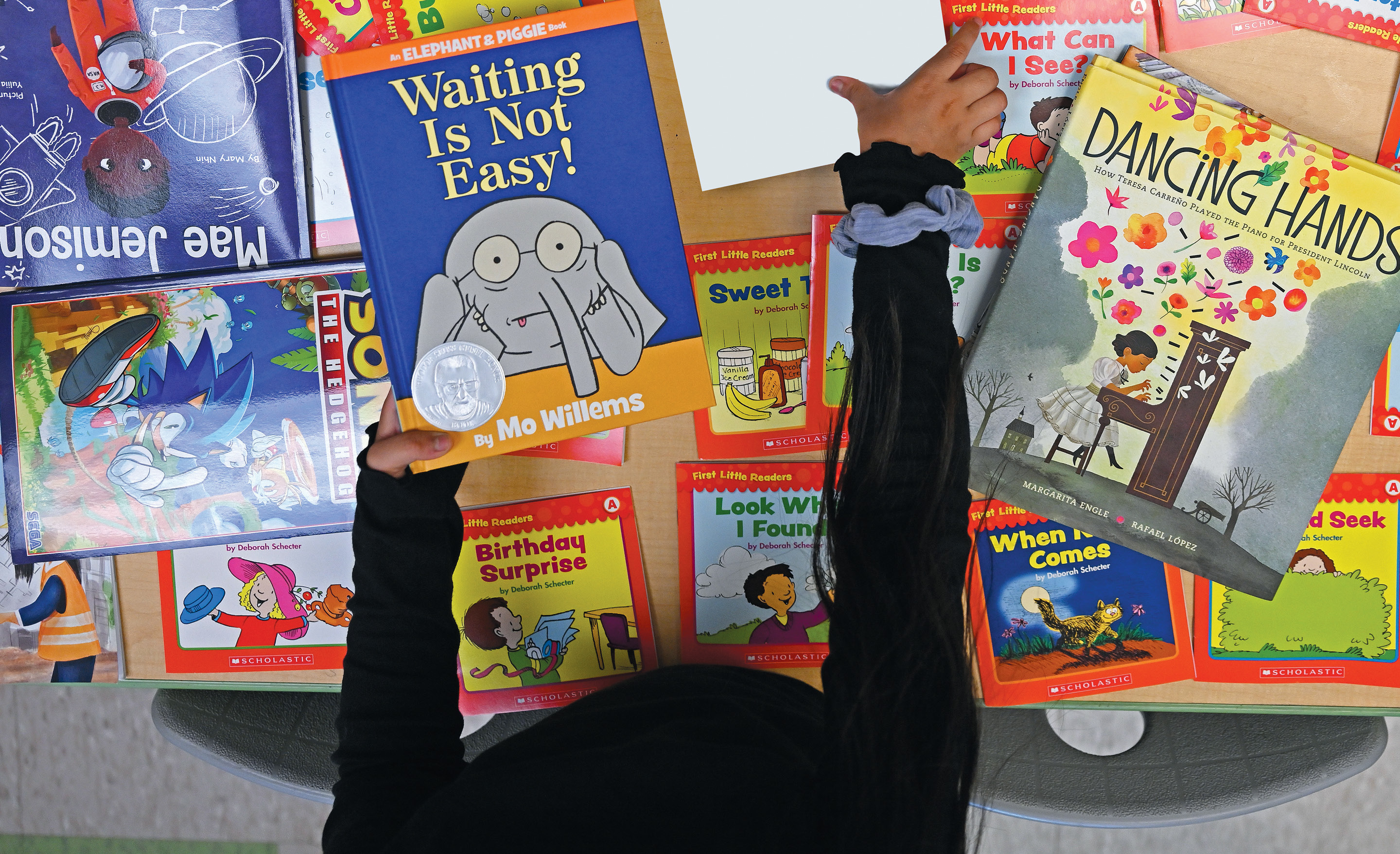

On a sunny morning in late April, Joseph Pimlott ’24, Ben Ramos ’23 and their classmates were sorting books into piles to prepare for their distribution at the beginning of May. Pimlott and Ramos, who were assigned to a fifth-grade classroom at Charles Barnum Elementary, stacked their books into the categories of Black Voices, LGBTQIA+, Latinx Voices, Native American and Indigenous Voices, Asian-American and Pacific Islander Voices, and Characters with Disabilities.

“The teacher had been trying to diversify her library, and we tried to identify some big hitting points she was missing,” Ramos said. “We also did a survey of some of the students and asked them, ‘What do you wish you saw in the library? Do you feel like the library represents you?’ Based on those answers, we tried to fill in some gaps.”

Pimlott added that some of the books they chose are ones they read in class, including When Stars are Scattered by Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed.

Ellen Paul ’07, executive director of the Connecticut Library Consortium, points out that there are three important legal differences between school libraries and individual classroom libraries, especially regarding attempts to ban books.

She named two court cases that enforced the precedent, Island Trees School District v. Pico (1982) and Case v. Unified School District No. 233 (1995). In the first case, a group of parents asked a Long Island school district to remove nine books from its school libraries, including Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut and Best Short Stories by Negro Writers edited by Langston Hughes. The group argued that the books were “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic and just plain filthy.” The district complied and five students sued, alleging that the removal of those books violated their First Amendment rights.

When the case reached the Supreme Court, the justices sided with the students, arguing “the First Amendment imposes limitations upon a local school board’s exercise of its discretion to remove books from high school and junior high school libraries,” and that freedom of speech meant that “school officials may not remove books from school libraries for the purpose of restricting access to the political ideas or social perspectives discussed in the books when that action is motivated simply by the officials’ disapproval of the ideas involved.”

Paul says, “What was really interesting about this decision is the differentiation between the classroom and the school library—a Board of Education may rightfully claim absolute discretion over curriculum in the ‘compulsory environment’ of the classroom, but a school library is a place of ‘voluntary inquiry.’”

That difference between voluntary and compulsory is what matters, she says. “Students have the right to receive information, and the school board can’t just remove a book from the school library, a voluntary institution, because they don’t like the ideas contained in that book. Books in classroom libraries, however, are generally considered to be curriculum materials and can be removed far more easily by local school boards.”

About a decade later, the issue reached the national level again when the Olathe, Kansas, school district rejected two books with LGBTQ themes for its school libraries. Several parents and students sued, and a federal district court found that the books were incorrectly removed because the Board of Education disapproved of the books’ ideology. It also found the school board had violated its own material selection and reconsideration policies.

As for those policies, every library has three—a collection development or selection policy that governs what is collected in the library; a maintenance policy that governs what is kept in the library and what is removed to make space; and a materials reconsideration request policy that outlines what to do if a community member requests that material be removed. Those policies do not exist within a classroom library, Paul points out.

Neither does the same level of privacy. “Privacy is a core tenet of the field of librarianship,” Paul says. “Librarians believe that all people possess a right to privacy and confidentiality in their library use, and the American Library Association and its affiliates, including the American Association of School Librarians, recognize that children have the same rights to privacy as adults.

So, a student can be confident when going to their school librarian or checking out a book from their school library

that that information will not be shared with others.”

She adds, “That right to privacy is really important, as maybe a child is exploring a book with LGBTQ themes and maybe is not ready to talk about that with others.”

One common argument made by book challengers is that parents should have the right to decide what their children read. On that, Paul says, “Parents absolutely should be having conversations with their children about what they are reading, and that is why we encourage parental involvement—but just because something is not right for your family doesn’t mean that it isn’t right for someone else’s family, and that’s the rub.”

Though she acknowledges that classroom libraries lack the same legal protections as school libraries, Paul says they play an important role and she applauds the work by Pezzetti and her students. “The proximity classroom libraries provide to books is definitely advantageous for children,” she said. “More books are always better.”