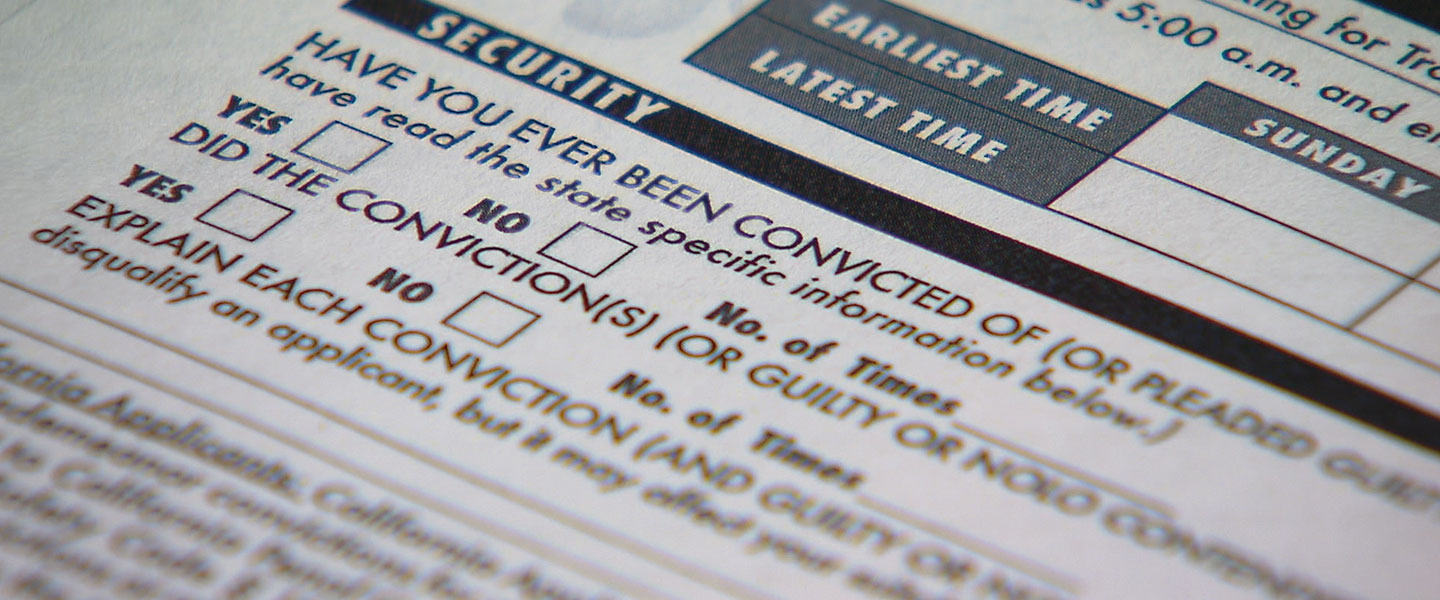

Since 2004, the grassroots movement to "Ban the Box"—the check box on applications that asks whether the applicant has a criminal record—has been gaining significant momentum, with 29 states and more than 150 cities and counties adopting some form of the ban. The laws mostly apply to public sector jobs, although some are now being expanded to include private sectors positions as well.

Most BTB policies don’t prevent employers from learning about an applicant’s criminal history at some point in the hiring process. But proponents argue that delaying that conversation increases the chance of employment for someone with a conviction. Critics of the policy, however, suggest the ban may actually put all black and Latino men at a disadvantage, because employers will make assumptions about their criminal status based solely on race.

So, do the policies work for the population they are designed help? To find out, Craigie used quasi-experimental methods to conduct a national study on the impact of BTB on public employment. She found that for ex-offenders aged 25 and older, BTB policies increased the likelihood of public-sector employment by nearly 40 percent. She also found no evidence of racial discrimination. (Craigie's research was featured by Inside Higher Ed as part of its "The Academic Minute" series in May.)

"We have a long way to go to ensure equal hiring standards for all who have been through the criminal justice system, but my study shows that at least in the public sector, employers are abiding by nondiscrimination laws, and Ban the Box is working," Craigie said.

That’s good news for individuals and for society, Craigie says, since employment is crucial for reducing recidivism rates.

"The streets are always ready to hire," Craigie said. "If we won’t hire them, if they can’t get food, if they have no access to healthcare, if they don’t have somewhere to live, what are they supposed to do? It’s not a black thing, it’s not a white thing, it’s not a Hispanic thing. It’s an economic thing."