The Ancient World

Firing high-tech lasers, Thomas Garrison ’00 uncovers earthly secrets hidden beneath the Guatemalan rainforest.

Thomas Garrison nearly unearthed an ancient fortress in 2010.

Deep in Guatemala’s thick jungle, Garrison was in the early stages of an archaeological excavation of the Maya kingdom of El Zotz, where a fortress—the likes of which had never been seen before—had been hidden under the dense brush for nearly 2,000 years.

“I was probably within about 100 feet of it and didn’t see it,” Garrison remembers.

The jungle would keep its secret. This time.

Garrison, an assistant professor of anthropology at Ithaca College, has been leading archaeological digs in Guatemala and surrounding countries since 2002 to study the mysterious Maya civilization, which reached its peak around the eighth century. After the Maya’s cities were seemingly abandoned around A.D. 900, the lush rainforest buried the ruins. For more than a century, researchers have been slowly uncovering these ruins and piecing together the story of one of the greatest civilizations in the ancient world.

In the dense landscape—Guatemala is said to mean “land of trees” in Mayan—it can take researchers years to map less than one square mile. But what if they could see right through the jungle?

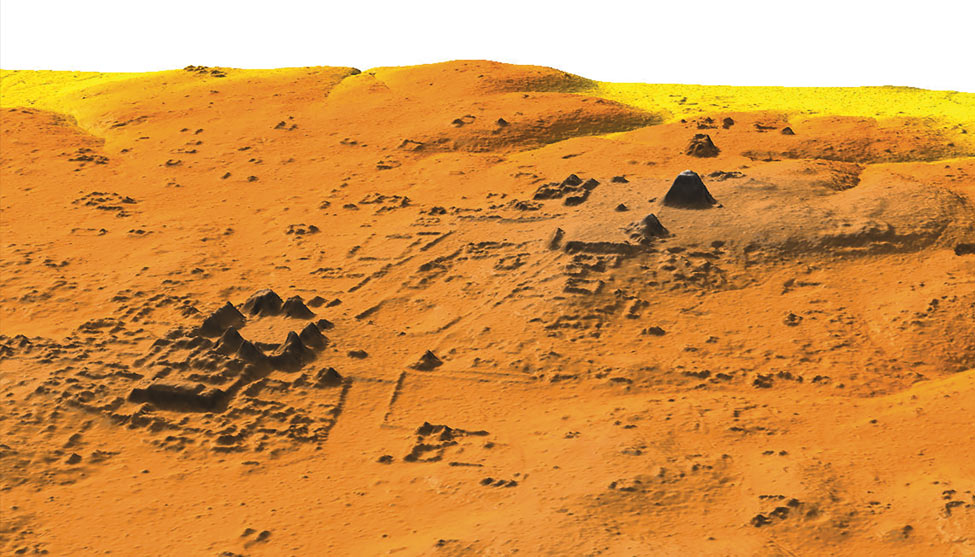

In 2016, Garrison and colleagues from Tulane University turned to a laser-based technology called LiDAR (light detection and ranging) that allowed them to do exactly that. By firing thousands of lasers per second from an aircraft into the forest canopy below, the scientists were able to map the surface of 800 square miles of Guatemala’s Petén forest.

What they discovered is changing just about everything we thought we knew about the Maya.

FIRST DEVELOPED to measure clouds in the 1960s—and then used by NASA to map the surface of the moon in the 1970s—LiDAR technology has been gaining popularity among archaeologists, especially in tropical areas. The vast majority—a full 92 percent—of LiDAR lasers bounce off the forest canopy, but the other 8 percent penetrate the treetops and brush, reaching the earth’s surface to create high-resolution maps that can detect slight changes in elevation to reveal man-made structures like buildings, roads and waterways.

“It wasn’t a matter of if we would find something with LiDAR in Guatemala. Our only question was: What we will find?” Garrison says.

But the technology is expensive, and Garrison’s attempts to secure a grant for the project were unsuccessful. So he and his colleagues went to the Pacunam Foundation, a Guatemalan cultural- and natural-heritage preservation organization that has been funding Garrison’s El Zotz dig since 2012.

“They decided that if they were going to do it, they were going to do it big,” Garrison says.

And big they went. With funding from Pacunam, Garrison and a consortium of scientists from around the world worked with the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping to collect data from nine archeological regions in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, in what amounts to the single largest survey in the history of Mesoamerican archaeology. The flights took place in July 2016. That November, Garrison went to the University of Houston to study the preliminary data.

“Immediately, it was clear there was an overwhelming density of new structures and settlements,” Garrison says. “I knew this was going to change how we think of the Maya.”

The final LiDAR data revealed more than 60,000 new structures, including new urban centers with large plazas, four major ceremonial centers, large palaces and, in Tikal, one of the most thoroughly studied of all Maya cities, a 90-foot-tall pyramid previously believed to be a natural hill. But it also revealed extensive roadways, intricate agricultural systems and numerous defensive structures, most of which were hidden beneath the trees and buried underground.

Known cities were up to 40 times larger than archaeologists had previously thought, in some cases encompassing what they had believed to be isolated settlements. Agricultural fields occupied large portions of the lowland seasonal swamps surrounding urban regions; in some areas, the Maya had even used drainage channels to convert wetlands into fertile farmland.

It all points to a more sophisticated and interconnected society than previously believed, a society with a much larger population, too. The new data suggests the empire supported roughly 10 million Maya, more than double previous population estimates.

“We knew they had agriculture—we’d seen some hints of fields. But now, instead of looking at individual sites, we are seeing whole swaths of land, huge patterns moving across Guatemala. We can put it all together and see how this ancient civilization functioned as a whole,” Garrison says.

“THE SURVEY is one of the most important developments in Maya archaeology in 100 years.”

The jungle—long the archaeologist’s great adversary—has suddenly become an ally.

In Europe and parts of Asia and Africa, access to archaeological sites is better and conditions are more favorable to digs. But for those same reasons, people have settled and farmed around and on top of ancient settlements, making it nearly impossible to get a full picture of their size, scale and interconnectivity.

“We’ve been behind because of the lack of visibility and the challenges of working in the jungle,” Garrison says. “Now, we’ve flipped the script—because of that jungle, we have one of the most well-preserved archaeological records anywhere in the world.”

Complex field systems in the outskirts of ancient urban centers likely would not have survived in other conditions. And without the LiDAR data, Garrison says, it’s highly possible they never would have been found in Guatemala, either.

“Even if we deforested the whole area, you could step right on them and never know what you are looking at,” he says.

The LiDAR data is so precise that Garrison and his colleagues can even see which sites have been looted and the crude paths looters have cut through the jungle to reach the sites.

Safeguarding and excavating the newfound sites—before looters find them—is incredibly important to Garrison and his colleagues. They aren’t sharing the exact LiDAR data, in order to protect the sites’ locations, but they do hope publicizing the findings will help them secure funding for future digs. And archaeological discoveries of this magnitude are worldwide news. When Pacunam announced the LiDAR findings in February, it generated headlines from Costa Rica to Slovakia.

Garrison was interviewed by The New York Times, the BBC, NPR, The Washington Post and The Associated Press. He also appeared in National Geographic’s one-hour special about the study, “Lost Treasure of the Maya Snake Kings,” which premiered in February.

It’s impressive recognition for an archaeologist still early in his career, and it all started at Conn. Garrison, an anthropology major and scholar in the Toor Cummings Center for International Studies and the Liberal Arts, first visited the Maya region as a junior. He studied abroad in Mexico, completing an independent study project in Chiapas using a collection of Maya artifacts excavated in the 1950s. He then used CISLA funding to travel to Belize to participate in his first archeological dig.

“I was pretty much hooked on this career, so my adviser, [the late Professor of Anthropology] Harold Juli, counseled me and pointed me in the right direction.”

Garrison used money he received as graduation gifts to travel to Honduras to participate in a dig that was run by Harvard professors, which, he says, “opened the door for me to go to Harvard.”

He was accepted as a Ph.D. candidate in Harvard’s anthropology program and, before he even took his first class, joined a team that would soon unearth a Maya mural. The significant discovery drew the attention of NASA, and Garrison had the opportunity to work with satellite imagery, setting him on a course to specialize in the application of digital technologies to the archaeological record.

“I’ve had a lot of things go my way,” says Garrison.

AMONG THE NEW RUINS revealed by the LiDAR data is the illusive El Zotz fortress. It’s one of a series of defensive structures that has Garrison and his colleagues rethinking the role of warfare in the development of the Maya Empire.

“We knew the Maya practiced warfare, but we hadn’t seen much in the way of defensive infrastructure,” Garrison says. “Now, it appears conflict may have been a lot more important to the emergence and development of Maya cities than we thought.”

While Garrison is planning to excavate the El Zotz fortress, the success of the LiDAR project has him thinking about other applications for the technology, too.

“I’d love to go to Brazil, for example, and take a look at the Amazon,” he says. “What’s under those trees?”

Garrison is also keenly aware that what is of no use to him and his colleagues—the 92 percent of LiDAR data that maps the rainforest—is a treasure trove of information for botanists, environmental scientists and those working to combat illegal deforestation.

“It has huge implications for understanding tropical forest environments,” he says.

Despite all that Garrison and his team have already learned, there is still much for researchers to analyze and thousands of new sites to excavate. The discoveries, Garrison says, have only begun.

“This data will provide a hundred years of work for many scientists.”