Professor Leo Garofalo travels the world to piece together the history of the African Diaspora in Peru’s southern highlands

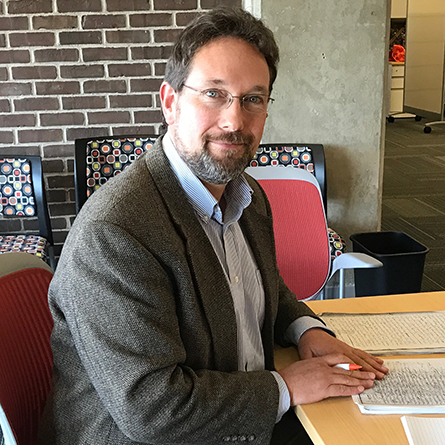

History Professor Leo Garofalo travels around the world to discover more about the African Diaspora in Peru’s southern highlands in the 1500s and 1600s.

Although much of the research into the topic of African Diaspora—including his own—has understandably focused on the Andean cities where the Black population maintained a majority into the 1800s, Garofalo’s recent work focuses on the comparatively under-researched experience of the African Diaspora in the Peruvian Southern Highlands, with a focus on the city of Cuzco.

“Black people—both free and enslaved—arrived to Cuzco at the same time the Spanish did, and they quickly became a significant and visible part of all aspects of life there, especially local religious practice and the development of colonial spiritual beliefs,” explained Garofalo. “In coastal Peru, there are very dynamic environments. You have Black confraternities, you have Black social organizations. In the highland areas, particularly when we talk about Afro-indigenous spirituality, we don't see what we see in the phenomenon on the coast. Therefore, you have to look harder and more widely for evidence of the African Diaspora in Cuzco.”

With fellowships to access Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library and the University of Chicago’s rare books library, as well as a research grant from the American Philosophical Society, Garofalo has studied several of the most prominent collections of records on the topic. He was particularly excited about being awarded a visiting fellowship from the British Library’s Eccles Centre for American Studies.

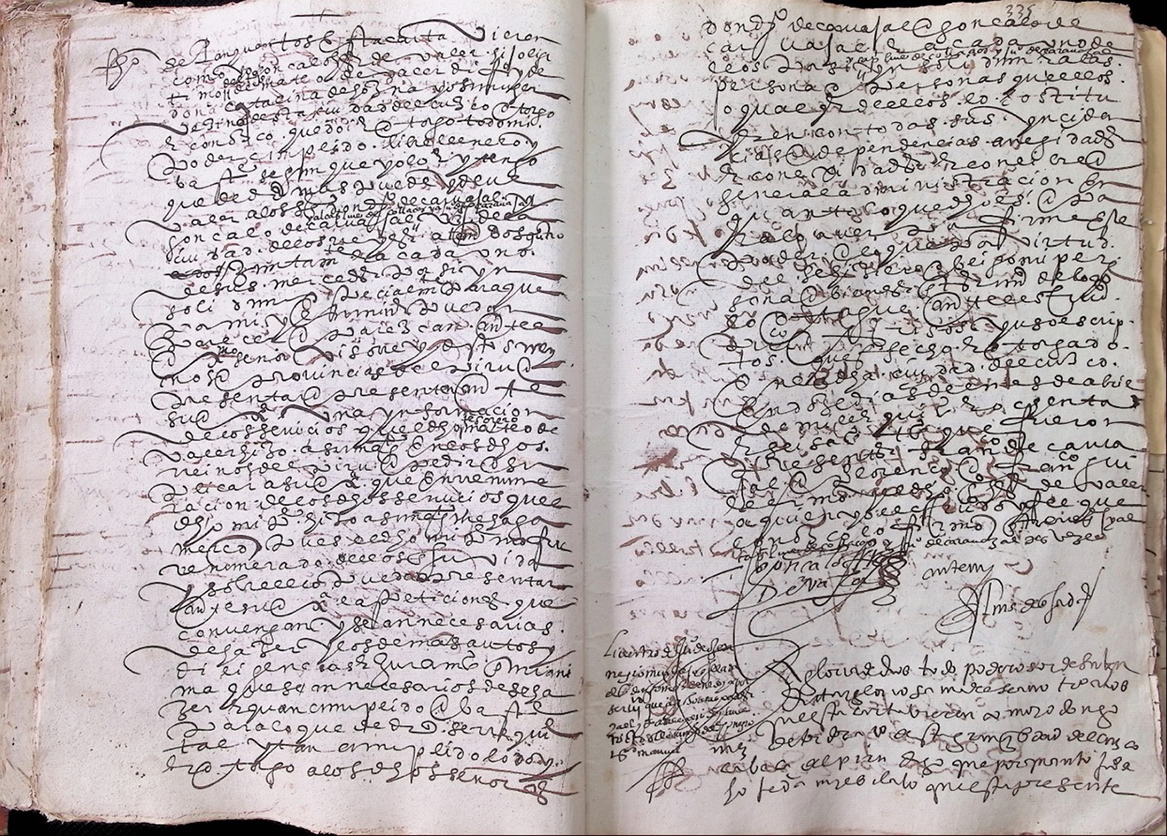

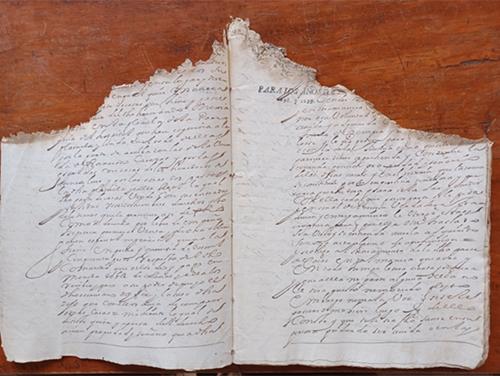

“The British Library has an unparalleled collection of material from all over the world and reaches back in time to the 16th and 17th century, which are the eras I’m working on,” enthused Garofalo.

Still, piecing together a largely unwritten 500-year-old history—by combining map and book collections with manuscripts—is by no means easy. “With original handwritten documents, you’re searching for needles in the haystack, right?” Garofalo acknowledged. “There are often no catalogs for manuscript materials, and, in some case, archives and libraries don’t have people who know how to read the early handwriting. They can’t even distinguish the dates. So, we don’t even really know what they have in an archive or a library’s manuscript holdings until we look through it all, document by document.”

This lack of information and the scattered nature of related documents has motivated Garofalo to pursue a secondary project as he continues his primary investigation.

“All this material really should be repatriated and put together in an entire collection, as opposed to broken into these little pieces in all these places,” he argued. “Most of us don’t have time to go around and look at little bits of these, so they get missed or ignored. So one of the things that I’m hoping to do with the manuscripts of the British Library and these others is begin to reconstruct a digital archive and then publish a printed copy of that as well. Maybe a shorter version, with translations to English to be used in the classroom. And so forth. Basically, trying to create a research tool.”

Garofalo hopes that his work will inspire others to dig into document archives in order to write the many still unwritten histories.

“Anyone interested can actually quite easily look at some of the highest-quality materials,” he said. “The websites of these libraries and their special collections have a small selection of other collections right there for you to look at. And with almost all of them, you can walk in and look at exhibits of rare books, maps and original manuscript sources. I encourage budding historians to do just that and begin their own journey.”